Logging with .net core and Application Insights

When you start builing serverless applications like Azure functions or Azure web jobs, one of the first things you will need to contend with is logging.

Traditionally logging was simply achieved by appending rows to a text file that got stored on the same server your application was running on. Tools like log4net made this simpler by bringing some structure to the proces and providing functionality like automatic time stamps, log levels and the ability to configure what logs should actually get written out.

With a serverless application though, writing to the hard disk is a big no no. You have no guarantee how long that server will exist for and when your application moves, that data will be lost. In a world where you might want to scale up and down, having logs split between servers is also hard to retrieve when an error does happen.

.net core

The first bit of good news is that .net core supports a logging API. Here I am configuring it in a web job to output logs to the console and to Application insights. This is part of the host builder config in the program.cs file.

1//3. LOGGING function execution :2//3 a) for LOCAL - Set up console logging for high-throughput production scenarios.3hostBuilder.ConfigureLogging((context, b) =>4{5 b.AddConsole();67 // If the key exists in appsettings.json, use it to enable Application Insights rather than console logging.8 //3 b) PROD - When the project runs in Azure, you can't monitor function execution by viewing console output (3 a).9 // -The recommended monitoring solution is Application Insights. For more information, see Monitor Azure Functions.10 // -Make sure you have an App Service app and an Application Insights instance to work with.11 //-Configure the App Service app to use the Application Insights instance and the storage account that you created earlier.12 //-Set up the project for logging to Application Insights.13 string instrumentationKey = context.Configuration["APPINSIGHTS_INSTRUMENTATIONKEY"];14 if (!string.IsNullOrEmpty(instrumentationKey))15 {16 b.AddApplicationInsights(o => o.InstrumentationKey = instrumentationKey);17 }18});

Microsofts documentation on logging in .NET Core and ASP.NET can be found here.

Creating a log in your code is then as simple as using dependency injection on your classes to inject an instance of ILogger and then using it's functions to create a log.

1public class MyClass2{3 private readonly ILogger logger;45 public MyClass(ILogger logger)6 {7 this.logger = logger;8 }910 public void Foo()11 {12 try13 {14 // Logging information15 logger.LogInformation("Foo called");16 }17 catch (Exception ex)18 {19 // Logging an error20 logger.LogError(ex, "Something went wrong");21 }22 }23}

Application Insights

When your application is running in Azure, Application Insights is where all your logs will live.

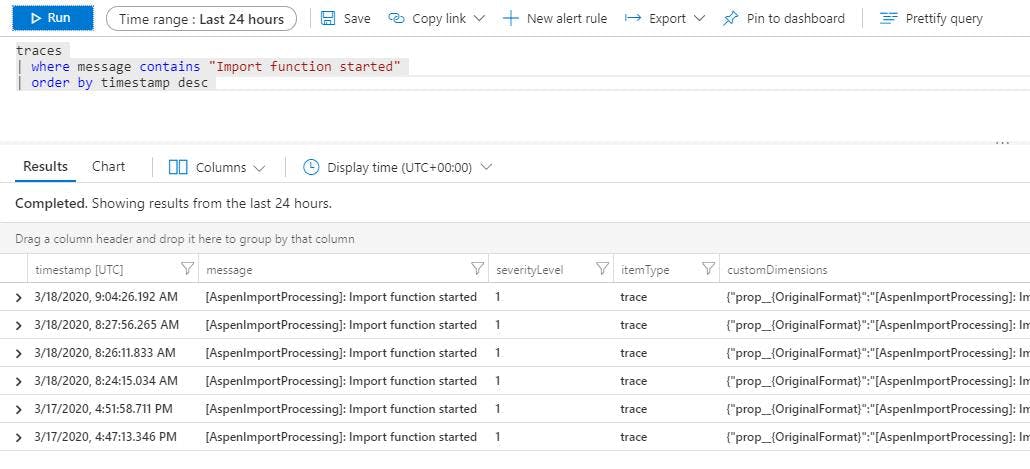

What's great about App Insights is it will give you the ability to write queries against all your logs.

So for instance if I wanted to find all the logs for an import function starting, I can write a filter for messages containing "Import function started".

Queries can also be saved or pinned to a dashboard if they are a query you need to run frequently.

For all regular logs your application makes you need to query the traces. What can be confusing with this though is the errors.

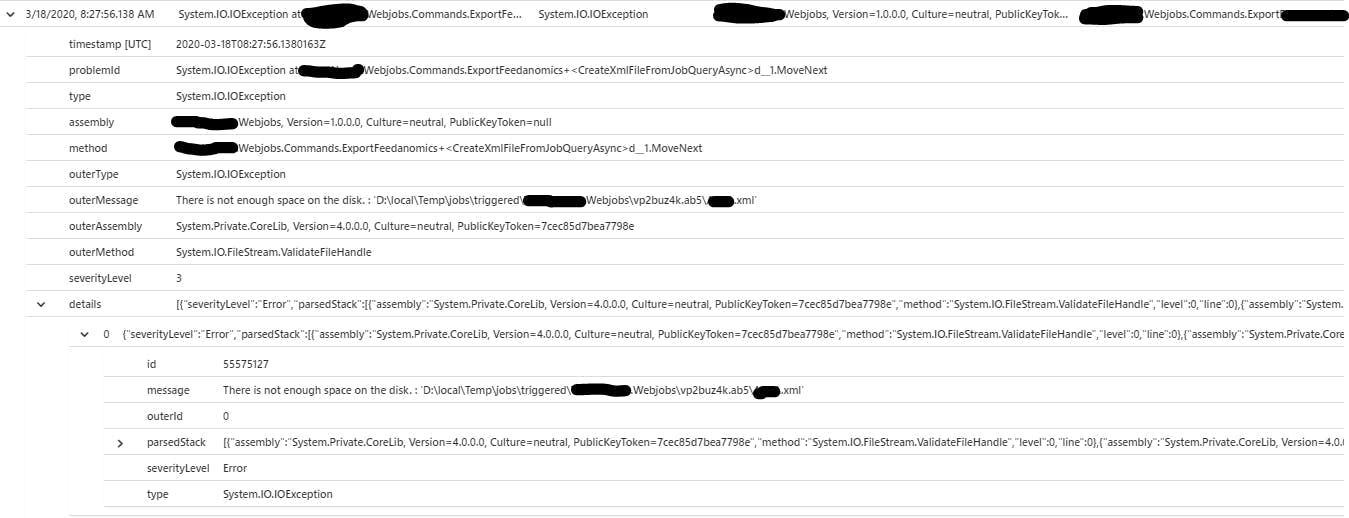

With the code above I had a try catch block and in the catch block I called logger.LogError(ex, "Something went wrong"); so in my logs I expect to see the message and as I passed an exception I also expect to see an exception. But if we look at this example from application insights you will see an error in the traces log but no strack trace or anything else from the exception.

This is just the start of the functionality that Application Insights provides, but if your just starting out, hopefully this is a good indication not only of how easy it is to add logging to your application, but also how much added value App Insights can offer over just having text files.